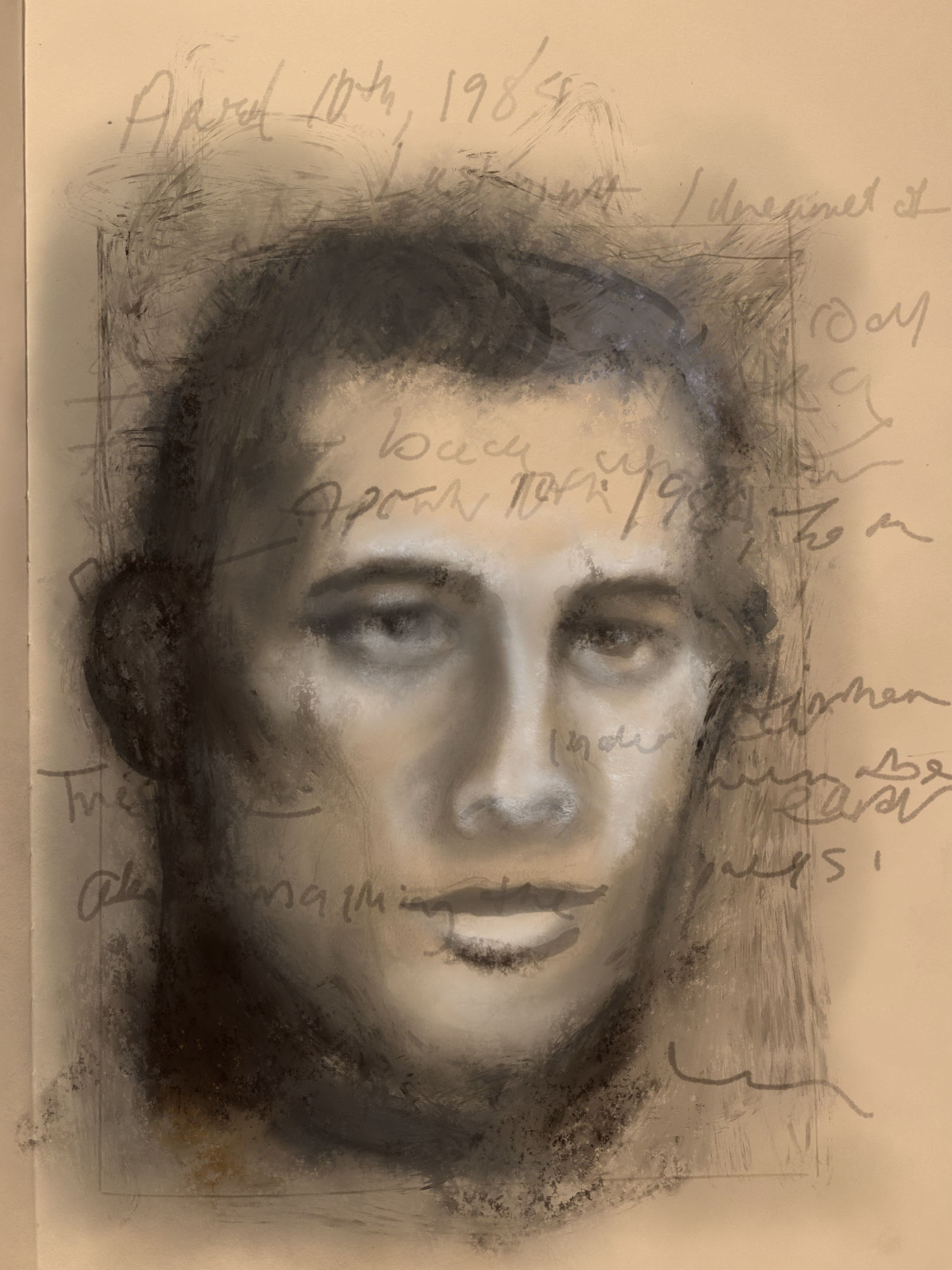

Flickers of the life of Allen Herring Jr.

The title of this project is “Shadows of the Seams”, as I view my ancestry as a series of shadows embedded in the seams of my past. I often choose not to shed light upon these shadows fearful of what it will mean for my sense of self. My connection to my great-grandfather seems like a shadow in itself as my memories of him are fleeting and are disappearing along with the grounding I feel to the place we both share as the backdrop to our childhoods. His memory has become lost in the seams of my mind which I try to keep in the darkness due to the painful history and narratives that reside there.

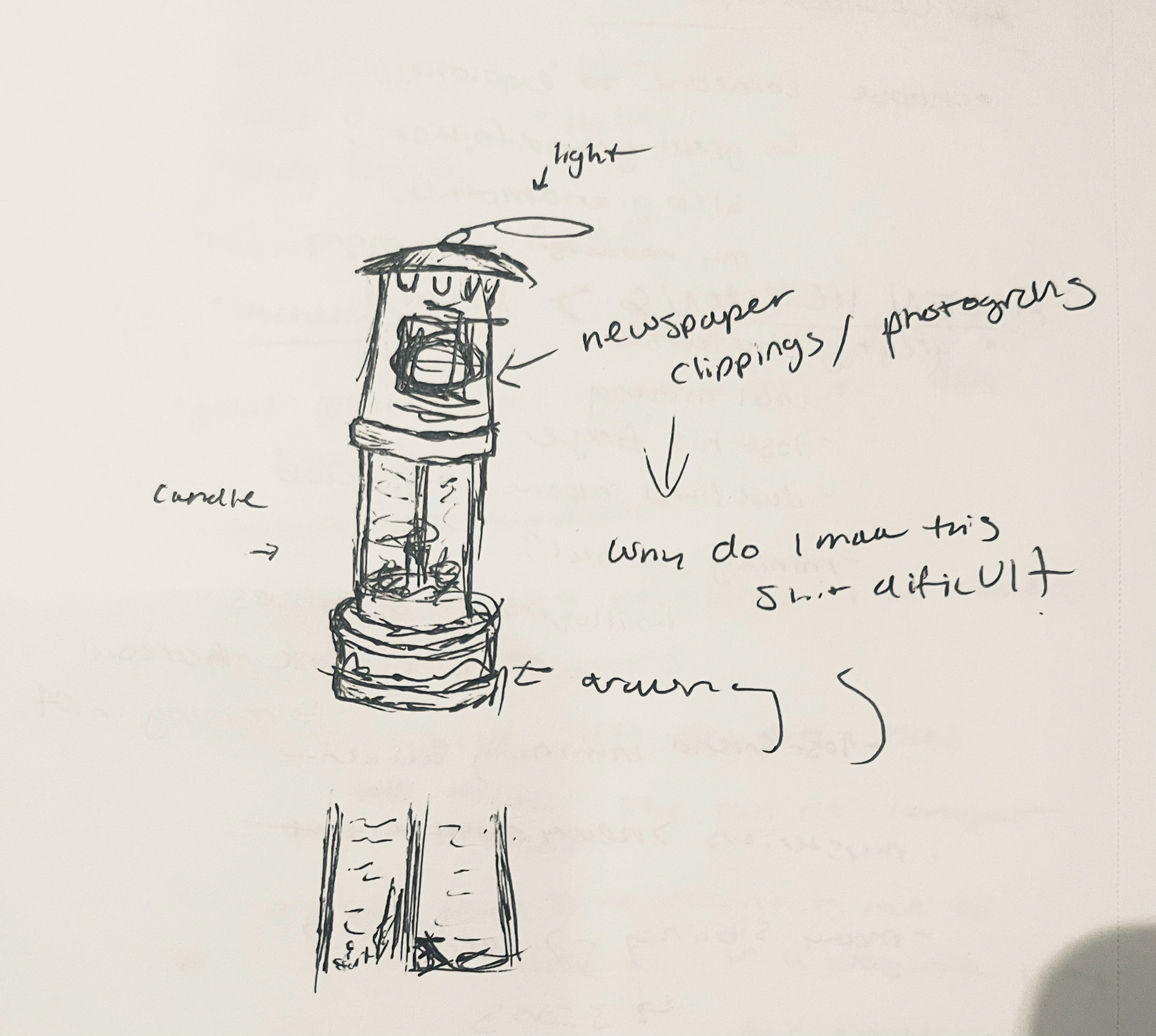

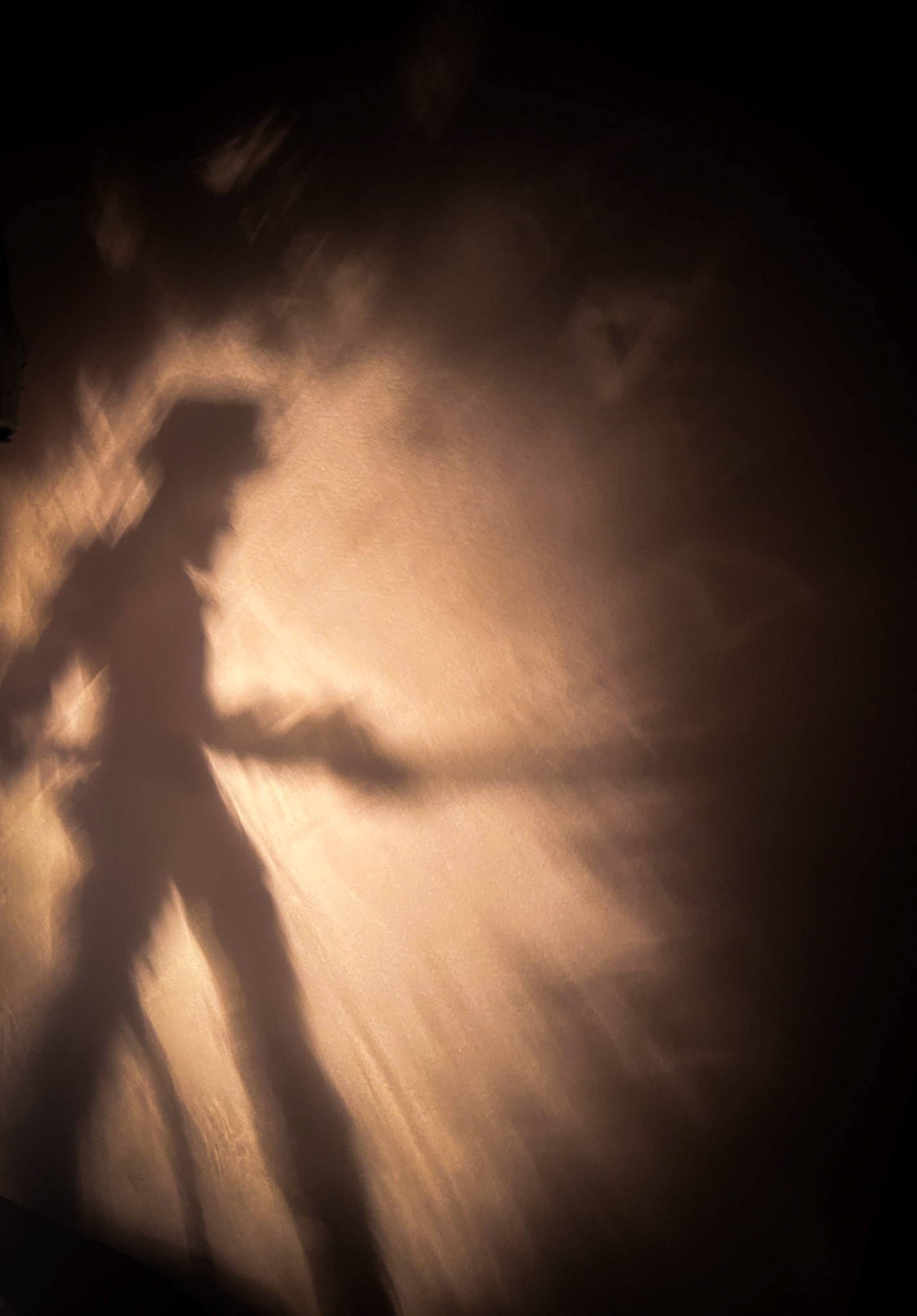

In the creation of both the journals from my great-grandfather’s POV and the visual product of his life, I had to shine light upon these shadows. I interviewed my great-grandfather over the phone shining light upon the history of the coal mining industry which is both painful in the way it has destroyed our environment but rich in the history and families it shaped. Recently and in my research I had to shine light upon these darker seams that weave through my mind and revisit the memories of my grandfather that ground me to my conflicted past. The creation and presence of the lantern symbolically embedded me into these shadows and when I turn it’s light on these shadows are reflected onto my walls. Through this reflection, the story and connection to my great-grandfather is kept alive.

INTRODUCTION & INSPIRATION

Three things come to mind when I think of my great-grandfather, his thick Pennsylvania Dutch Accent, his smile, and the fact that he taught me my first curse word (shit). My great grandfather, who others call Pop but to me was always Pappy, was a man of few words. I don’t know much about him, something I will probably come to regret, but the few memories I hold with him are special. Something about his weathered appearance, his hands rough from years of labor, ground me in the culture of my hometown. Despite having lived in the same area his whole life his eyes expressed a wisdom that extended beyond the borders of Schuylkill County. A wisdom that can only be gained through years of hard work.

The mining industry is often melted down and rallied against as a harmful aspect of history. Something that has burned radiating heat into our world for years choking our air with pollutants. I don’t think coal should be burned any longer but I also acknowledge a deep-rooted culture behind the product. I see whole towns and communities that sprung up because of this industry. I see a rich history grounded in the stories of generations who labored in the ground below. The tunnels left empty but echoing with the clang of tools which was later replaced by the whir of machines. I see the streets of Centralia abandoned after a mine caught fire the sounds of a bustling community lost in the smoke that rises from the ground below.

My pappy worked as a miner for about 30 years. Leaving his family farm in his 20s to work picking rocks from the coal that ran from the mine below. He would then learn from another miner how to tackle the harsh underground world. He would put up timber to support the ceiling, fill holes with dynamite, and blast to reach the coal. When I spoke to him about his work in the mines my dad asked if he was scared. He paused for a moment before simply stating.

“No, I was never afraid in the mines”.

My dad always says “pop” is his hero and as I reflect on my Pappy’s life both his past and my memories of him, I can’t help but agree. I would sit at my great grandparent’s kitchen table eating Scooby snacks and he would come home, at the age of 70, after a long day working at a lumber yard. As a child witnessing a 70-year-old man working beyond what most would consider a traditional retirement age in America, caused the idea of retirement to be obsolete from my vocabulary until I got older. He would sit down at the table and eat a slice of one of the pies my grandmother made weekly, perhaps strawberry or coconut cream, listening intently while I rambled on about whatever picture I was drawing with the large box of Crayola crayons my grandmother kept. In the evenings he would sit in his recliner and watch the news while I would drive toy cars on imaginary tracks paved on the carpet below. He would endure hours of my ramming the little metal cars into the coffee table or driving them over imaginary tracks on the patterns of the arms and headrest of his recliner. One day I pushed him beyond his admirable tolerance level of me dropping cars onto him but instead of lashing out in harsh Pennsylvania Dutch, he calmly stated,

“Mikayla, you’re going to be on my shit list”

At the time, shit was not in my vocabulary. But thanks to my Pappy, from that moment on I would proudly declare “Shit!” whenever it felt appropriate.

He wasn’t a big talker unless it was about hunting, scrapple making, or cutting the grass. Therefore during the rare moments where he would speak, I would sit with an attention span I rarely showed. I remember a particular time when I was working alongside him making doughnuts in the basement of my childhood church. The older men swapped stories back and forth in heavy Pennsylvania Dutch accents sharing laughter and wide smiles that you would rarely see in this group of harsh-looking but extremely kind-hearted people. The thump of the donut press accompanied their stories of growing up in the area often knowing each other since they were boys. They made it seem as if all of the world’s excitement could be found in the stretch of a couple miles of Schuylkill County. Those stories and laughter filled that church basement creating a memory that I cling to.

Years later that basement would be painted over in my mind by an experience that destroyed all of the good memories held in that space. My pappy’s voice and the smell of fashcnauts faded into a part of my brain I couldn’t access.

Gone were those Pennsylvania dutchies I grew up with replaced by a malevolent force whose presence in my memory took away any belief that men could be kind. It wasn’t until November 2023 when I was sitting in a small room during a week-long trauma treatment that this memory would come back. I played the scene of the basement dissolving into a world of pain and fear over and over unable to reach the carefree child I once was. On day two it came back to me, my therapist’s voice breaking through the terror encouraging me to reach further into my mind, replace the bad with good, and grasp for a memory of better times drowned in a pool of evil. A faint sound reached my ears, the unmistakable sound of a Pennsylvania Dutch accent and a familiar laughter ringing out. It was my Pappy’s laughter and it is the thing that allowed me to access years of good memory I had been psychologically denied of. It is his laughter that allowed me to conquer a small fraction of my mind. It was his laughter that gave me a fleeting feeling of power to push aside the bad memories that polluted all the good.

My Pappy’s laugh is a sound I can distinctly bring to mind as it fills the whole room. It is the kind of laugh that is rare and never forced. It rings out through the room and is accompanied by a wide smile that causes the sides of his eyes to crinkle and his cheeks to lift. His smile is one of my favorites and I captured it once on my first digital camera. His eyebrows lifted high the smile reaching his widened eyes. I’m glad I captured it. So one day when he is gone and his laughter will only be a sound I can hear in my mind I can look at that picture and remember it more vividly.

I didn’t spend a lot of time with my pappy, though notably more than I have with some of my other grandparents, but he has undeniably helped me become the person I am today. He passed down a hard work ethic that allows me to excel in school. He taught me that turning 50 does not mean I have to retire and sit around waiting for death. He also taught me that it’s okay to just sit in a recliner and rest, an invaluable lesson that I should use more often. I see myself in the way he can sit for hours without talking but spontaneously make a comment that causes the whole room to laugh. The memory of his voice and laughter allowed me to start retaking power over the trauma that I allowed to consume me for too long. In doing this project I have learned so much more about my connection to him. He is one of my heroes and though his life was simple it is a story of inspiration.

SETTING THE STAGE: A FREE WRITE

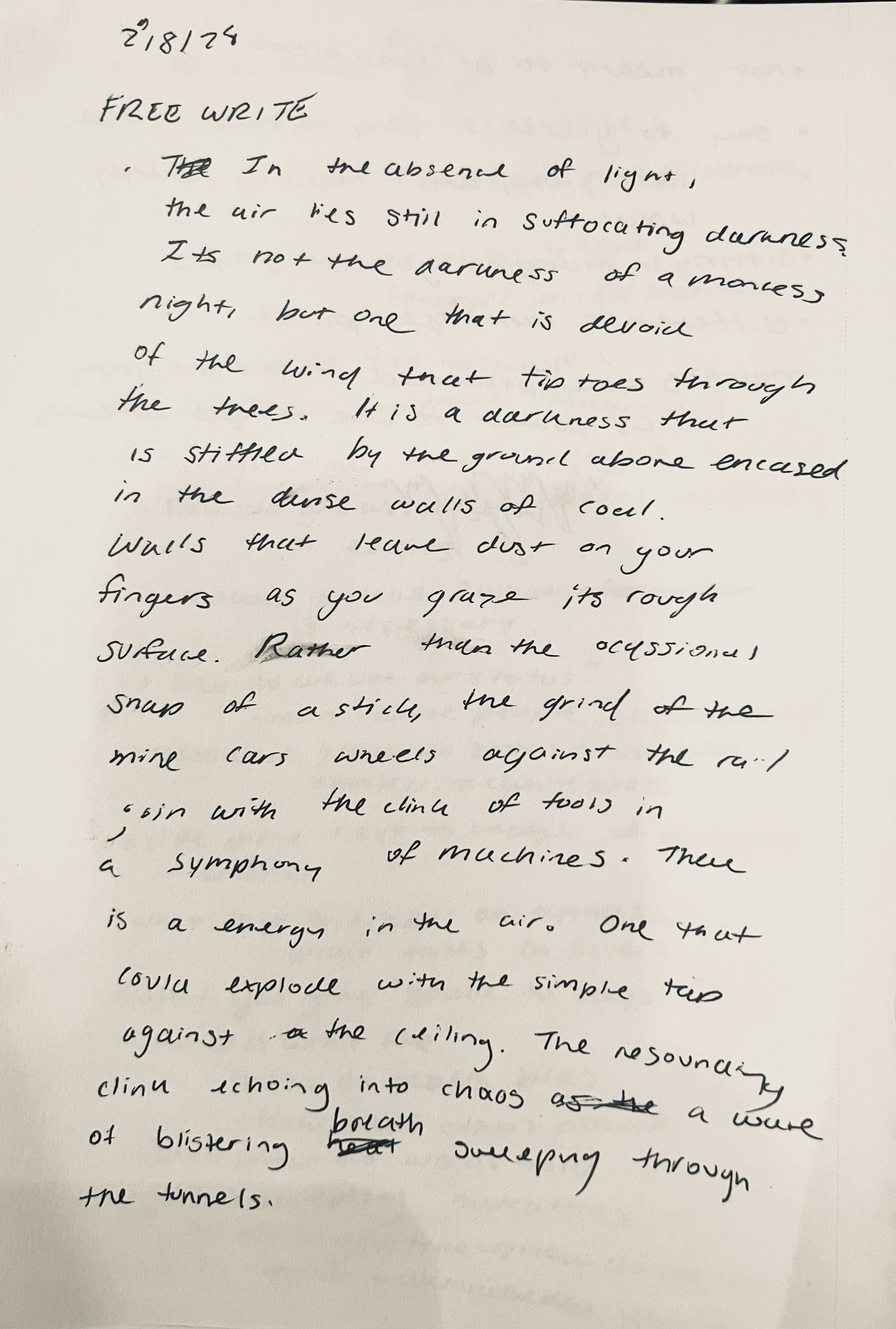

The free write prompt I was given was to immerse myself in an environment or place from the text. I choose to write about what I would imagine being in the coal mine was like in the absence of light. This brief piece is a stream of consciousness in which I allowed the coal mine in my imagination to spill through the ink of my pen.

2.18.24

In the absence of light, the air lies still in suffocating darkness. Not the darkness of a moonless night, but one that is devoid of the wind that tiptoes through the trees. It is a darkness that is imprisoned by the ground above the weight of the world supported by the dark walls of coal. Coal that leaves dust on your fingers as you graze its hardened surface.

Replacing the occasional snap of a twig, the grind of the mine car wheels against the rail joins in dissonance with the clink of tolls in a symphony of machines. There is energy in the air. On that will explode with the simple tap of a hammer against the coal. The resounding clink echoes as an eerie ring of the chaos that will follow. A wave of blistering breath swept through the tunnels scorching everything in its path. A single spark bursts into a fire that will linger in a ghostly smoke rising from the pavement. Swirling through the air creating figures that will replace those that once roamed. The smoke reminds us all of the world men once wrestled with below. A legacy of history changing and changed. Sweltering summers fueled by ground mined long ago connect us with binds of rage and admiration.

STORIES FROM THE SEAMS OF THE EARTH

The following series of journal entries were written from the imagined pov of my great grandfather. I tried to place myself in his shoes, connecting consciously to the work of a miner. An industry I despise but wanted to walk the trails of myself. Connecting with a history that shaped not only my family but the communities around me.

Friedensburg PA, 1980s

Monday morning April 9, 1984

I woke up at 5 am this morning. I am currently sipping my coffee, a bitter black brew to start my day. I’m a man of few words but I have many thoughts so I bought this little black journal to jot them down.

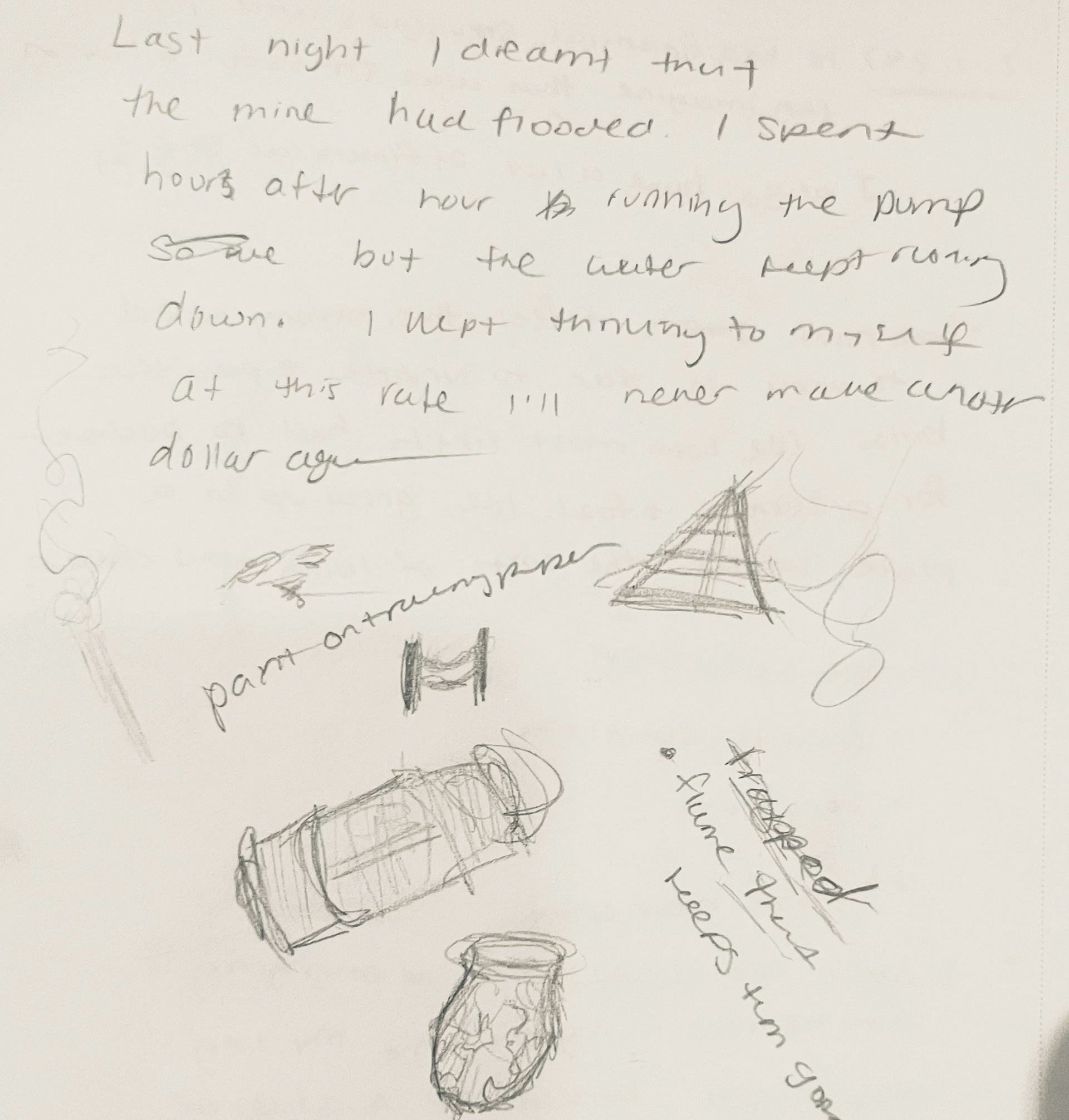

The wind was brutal last night through the top floor we occupy above the gun club, howling through like a train shaking the floorboards. I don’t mind the wind but it was the soft patter of rain that kept me up. Rain running into the mines means we will have to spend the whole day pumping it out. A day of pumping means a day without pay.

Last Sunday I had to spend all afternoon sitting there with that pump so we could go back to a steady stream of coal on Monday. I took my grandson Wayne with me and we sat in the little coal shanty playing cards, the hum of the pump fading into the background. Wayne is now eight years old, with thick eyebrows and eyes as dark as the coal I mine, a sure sign that he is a Herring boy through and through.

But enough writing I have to be up in Hegins by 7 am and get down into those coal seams.

Monday evening April 9, 1984

I got home at 3 pm today after a disheartening day of running the pump. Today is a famine day, the result of the coal belts running empty today. Being an owner of a small mine has its good and bad days or as my wife Mary refers to feast or famine days. As we counted our money each crumpled dollar I lay down on the table my heart slowly began to sink as I realized we would have to dip into our savings to make it through this week. The mines are both a place of prosperity and emptiness. To make ends meet, this weekend I will drive the little red Chevy down the winding roads around Pinegrove. My customers buy the mine-run coal, a supply of whatever the ground decides to give that day. Some of the chunks are big and blocky while others are crushed into finer bits. The coal breaker washes them and cuts them to sizes our local customers will select to burn in their home furnaces. It is not much but these weekend runs supply a stream of income when the coal decides to hide behind the rock.

Tuesday Morning April 10th, 1984,

Last night I dreamed of the day the coal fell on my leg. It was back when I was assisting a miner building my skills in tackling the harsh underground workplace. I was drilling holes when the constant whir of my drill was interrupted by the sharp creak of wood. A sign that the wooden timbers were about to crack under the pressure of the earth above. Rocks rain down from above smacking off the top of my hard hat the light of my lantern producing an eerie flicker as dust chokes the air. I can’t move, not because I’m afraid, but because a large rock has landed on my knee. In my dream, I couldn’t physically feel the pain but I recalled the feeling of being trapped. For a moment I thought I would never emerge from the tunnel into the light above. To a miner seeing the light at the end of the tunnel is not a sign of the end of life but the assurance that they survived another day laboring in the world below.

Tuesday later in the morning April 10th, 1984

I’m taking a brief break while a safety check is run. I hold my breath as the roof is struck hoping to not receive a hollow echo back but a sharp strike indicating that the low ceiling above will remain solid. I keep thinking about my dream as if it were an omen, a signal that something is about to happen. I drilled about 4 holes already and loaded them with dynamite yelling “Fire!” before the whoosh of the dust filled the air. The stream of coal is running like the river today so hopefully, that means extra money to put in Wayne’s savings. I should get back to work and try to blast seven holes today. There is no room for fear in the mines only hard work and caution.

Tuesday evening April 10th.

There was a Gas Explosion at Honey Coal Company today. The place where I was working in my dream. After blasting a hole they didn’t run the fans that would dilute the methane beyond its point of deadly explosion. The air was left choked with gas sitting there waiting for the spark that would set it off and give it the energy to explode. The miners went down, the bell rang echoing through the tunnels as a signal to continue working. However, this time that echo was the sound of disaster. The gas was struck with the clang of the bell and the methane exploded in a hot wave of coal dust sucking the oxygen out of the air as it runs through the tunnels. Many men were burned badly, men that I had previously labored with. I could have been one of those men. It was only a couple of weeks ago that I stopped working there. I could have been the one who returned home, my face disfigured by the scorching heat of the dust. I have never been so grateful to return home my face only masked by a layer of black dust.

Despite the news life went on as usual. I returned home in fresh clothes but my body was still stained by the day’s work. I left my soiled work clothes in the washing machine we keep in the basement specifically for my dirt-soaked attire. I glanced at the bucket of nails Mary had collected from my pant pockets. I went upstairs and sat down to a dinner of thin potato soup the warmth of it cold in comparison to what it must have felt like to have scorched wind of coal going down the throats of those men. I will go to bed at 7 pm as always and this time probably fall into a dreamless sleep before I wake up and repeat it all over again.

Wednesday, April 11th,

If someone were to ask me what I think about I would tell them I don’t have a lot of thoughts. The truth is I do, I just don’t say most of it out loud. On my way to work, I think about the farm I grew up on just down the road with my nine siblings. The white farmhouse where my mother made sauerkraut and where I learned to make sausage and scrapple from the wild game we harvested. I was 19 when I married my wife, who was 17, in Summit Station. Two years later we had our first son Wayne Herring Sr. who went off and joined the army leaving his son Wayne Jr. in our custody. Wayne Jr. is the first thing I see when I emerge from the grounds below. His small silhouette is framed by the light as my eyes adjust after hours of being in darkness. Sometimes I wonder what he will grow up and be. What will his job be, will he have children, and will he be proud of me?

I figure I will probably always work in the mines. The business that brought life to an area otherwise kept alive by tight-knit family farms. I wonder how much longer the business of mining will be kept alive. In the 50s when I started working about 100 thousand men were working underground but that number has been reduced down to a little over 30 thousand today. Most underground mines like the one I run are closed. Small family-owned mines are swallowed up by large anthracite companies. When I was 20 I started as a coal picker extracting rocks from the coal but that job has been replaced by a machine only needing to be operated by one man. I don’t know how many more years I will spend under the surface of the earth amongst the coal seams that weave through the tunnels blasted out both by generations past and present. I enjoy the mines. The underground world with a climate of its own, cool in the summer, and warm in the winter. A symphony of machines created by the instruments of miners. The clink of a hammer against the ceiling, the rumble of the minecar wheels down the track, and a slow trickle of water running down from the surface ahead connecting the above here below. I find a rhythm as I work with the endless seams of black coal running through the ground until it’s time to emerge into the world above again. The smell of decaying leaves replaced the smokey dust of coal. The Pennsylvania air whispering against my coal-streaked face signaling that I have made it out of the mines to go home once again.

ILLUMINATING THE SHADOWS

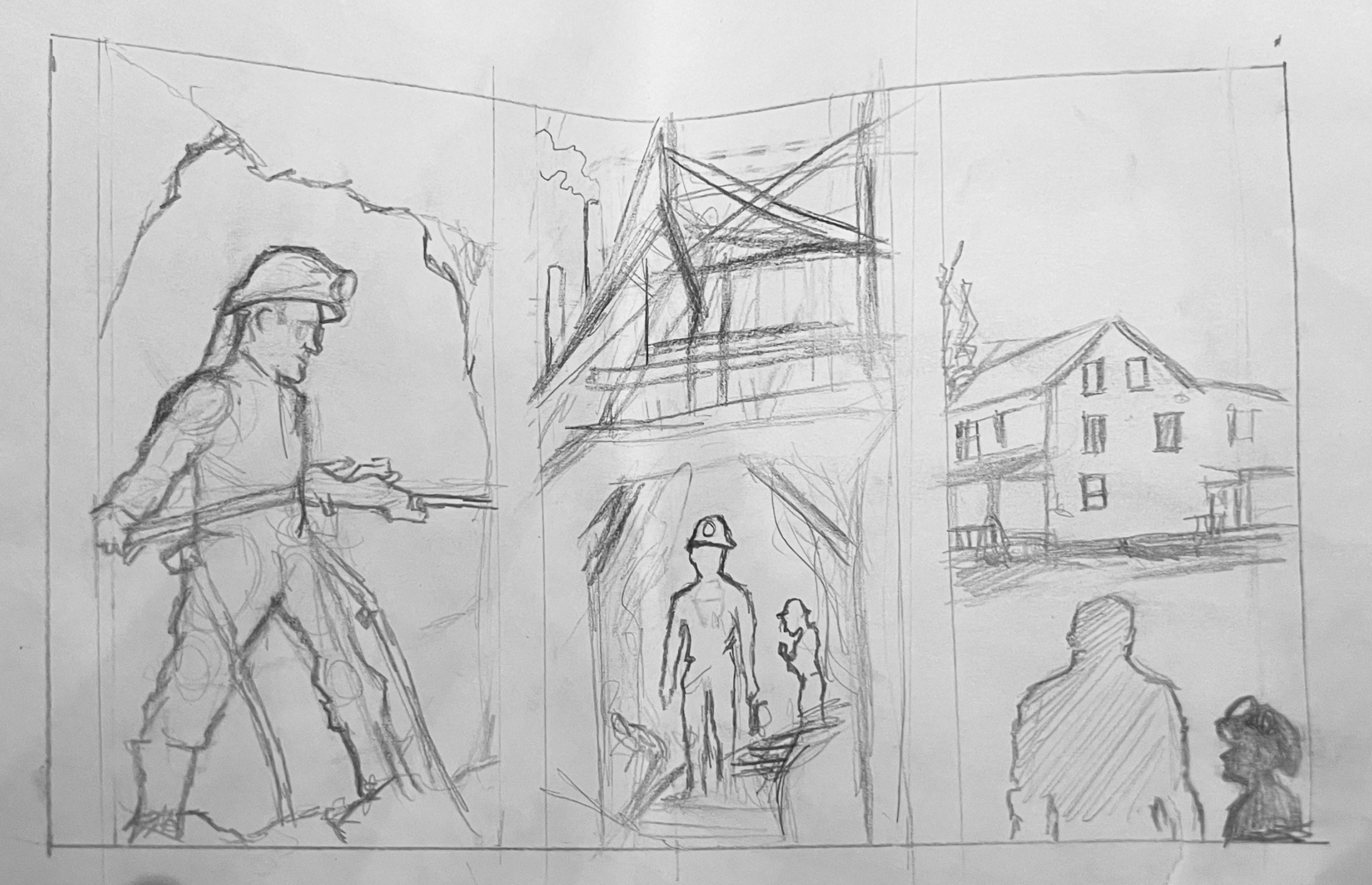

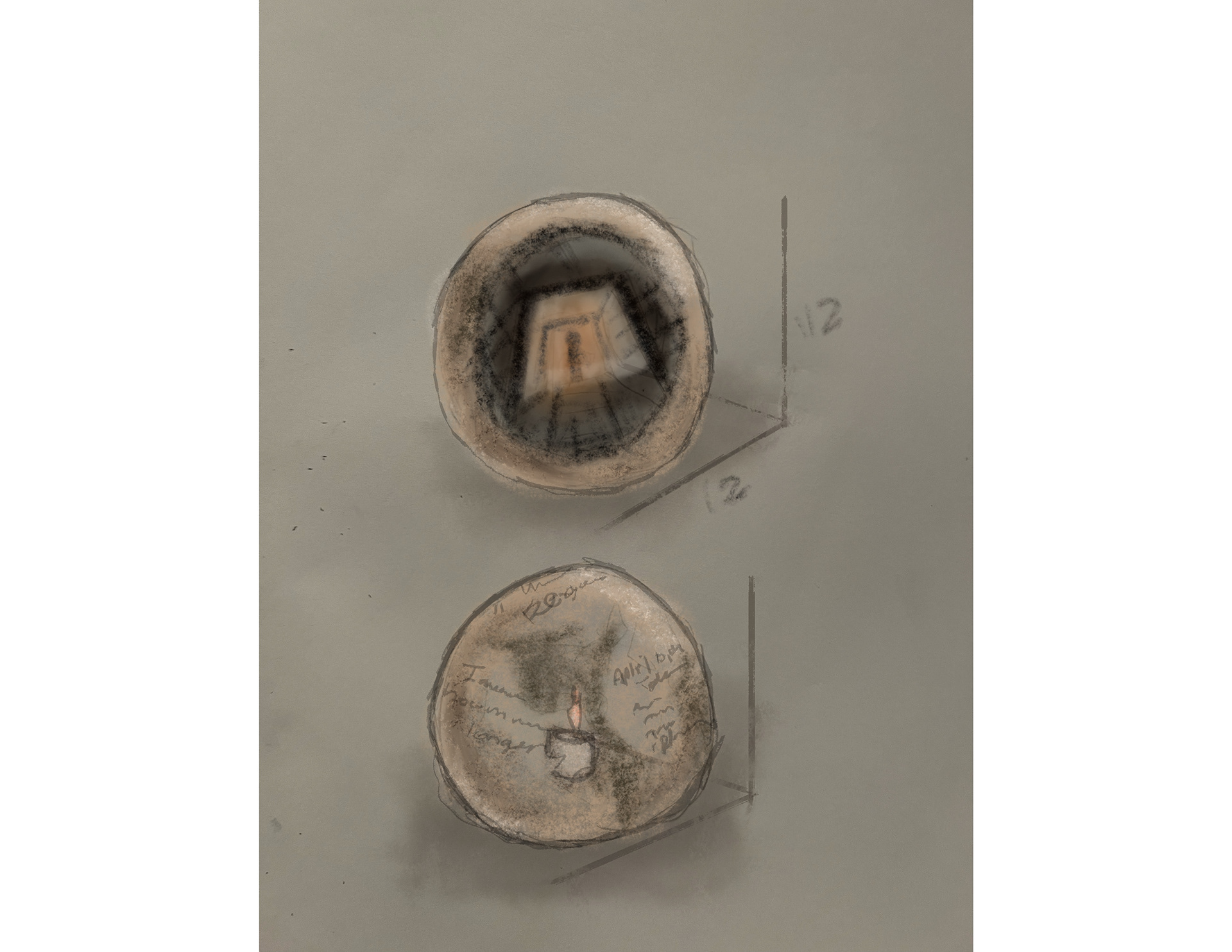

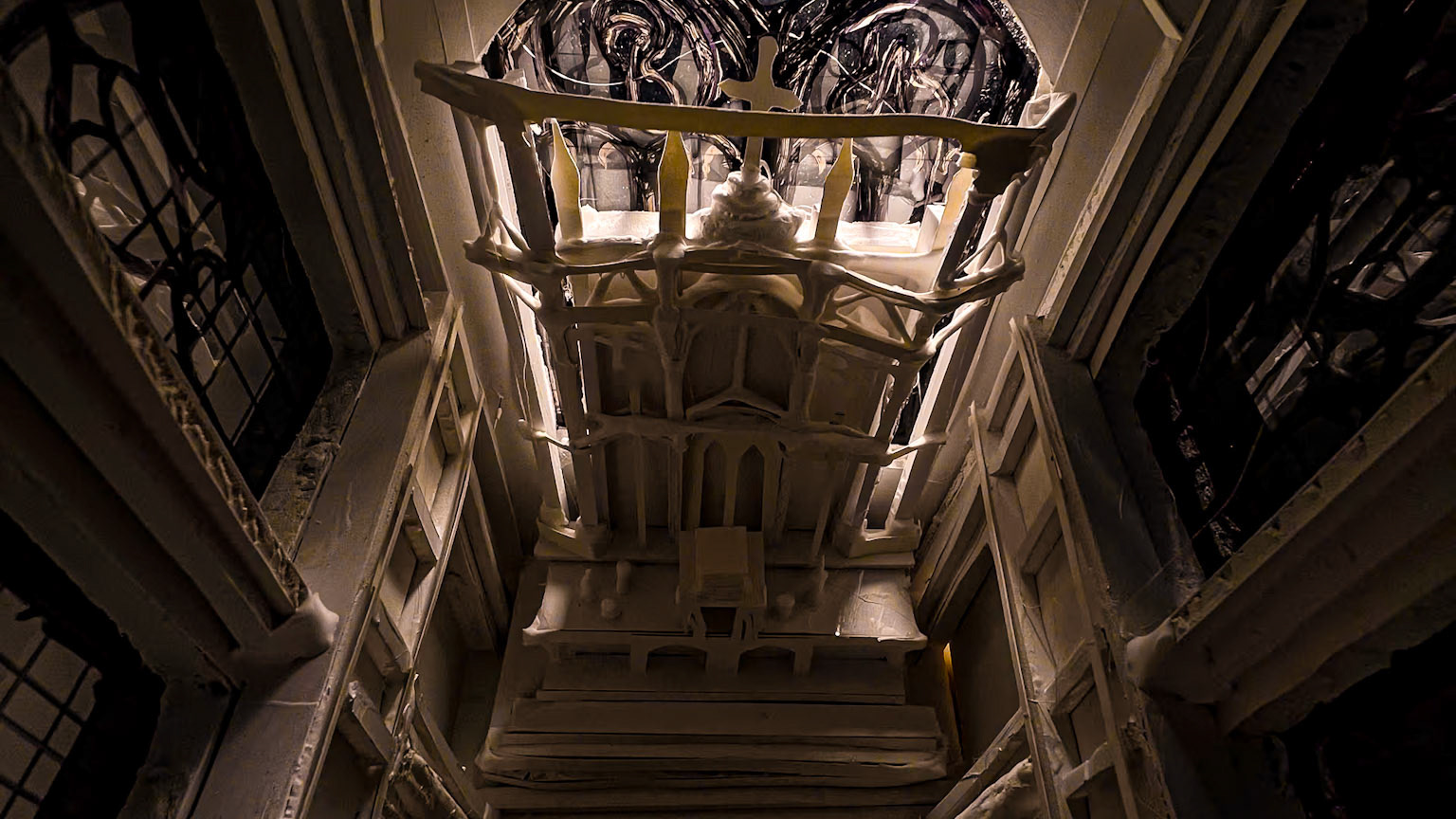

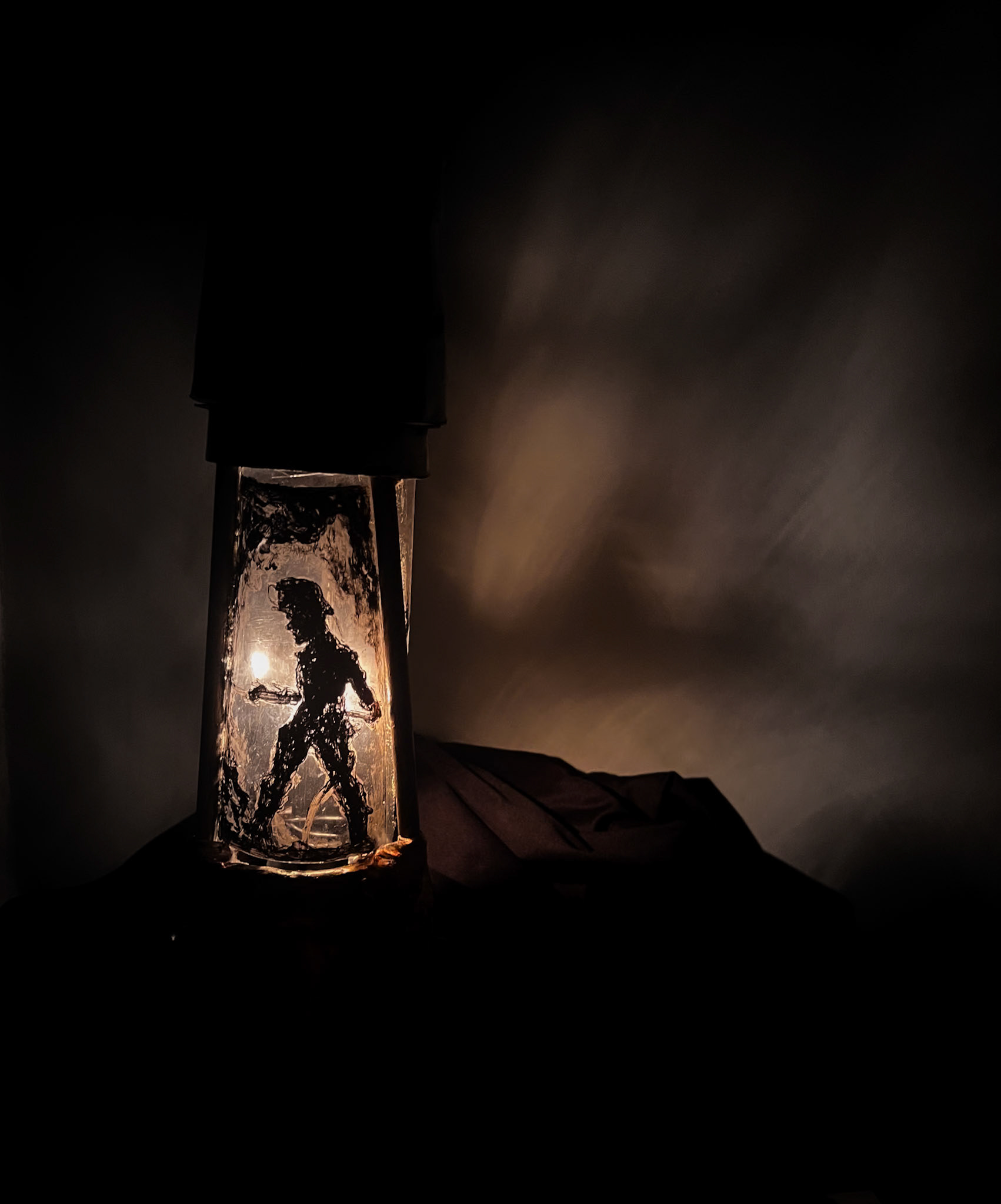

Lanterns were essential to the work of miners in the pitch-black underground world of the coal mines. While this is not the lantern model that inspired this piece was not one that my grandfather would have used, the structure was not only a practical form for my vision but also connected his story to the history of coal mining. I was inspired by the silhouette work of Kara Walker and her utilization of shadows to tell stories. I painted silhouettes onto mylar film which would be the shadows cast onto the surrounding surfaces by a lightbulb. The silhouettes transition from a scene of my grandfather working in the mines to him coming out, ending with a picture of him and my father as a boy walking towards the Friedensburg fish and game club they resided in. My father is wearing my grandfather’s mining helmet looking up at his grandfather with pride.

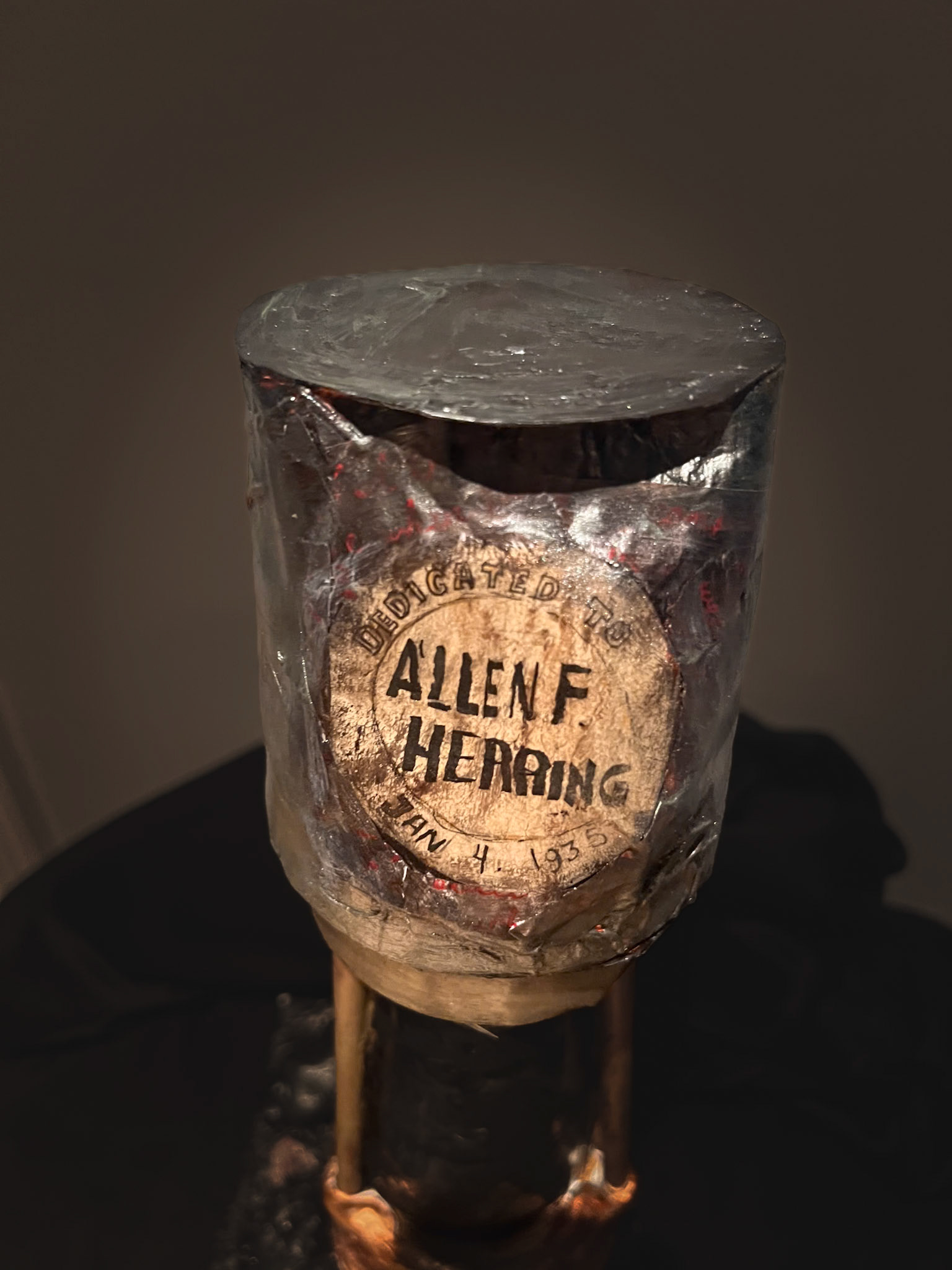

The base of the lantern was formed with layers of paper mache and strips of the journals I wrote from my Pappy’s pov. If you look closely a photograph of him taken when he was younger is pasted onto the base but painted over to give it an aged and ghostly feel.

Surrounding the lantern is a form created by paper mache and black paint. I wanted the base to look like the bottom of mine and form around the lantern embedding the object into an environment where it would have been used.